Gabriel Collins, Tony Payan, and David A. Gantz

Original report accessible at: https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/quantifying-investments-mexico-china-linked-entities

Investment Dataset available at https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/u/0/d/1UYt0yITDmZTxDwzAz5UWfl2cE731nG9ZMiyiQVEl01k/htmlview?pli=1

I. Executive Summary

In a world of increasingly fragmented globalization, access to premier markets on preferential economic terms will be a core strategic priority for export-oriented industrial countries. The People’s Republic of China hosts by far the largest collection of manufacturing capacity anywhere in the world and this multitrillion dollar factory floor faces a three-way choice as domestic consumption stagnates in China: (1) export into an increasingly protectionist world where goods will face steeper tariffs, (2) shutter facilities and lay off workers, or (3) find economic permissive portals where manufacturing and final assembly capacity can be reconstituted offshore behind tariff walls and thus enjoy preferred market access.

China’s growing manufacturing investments into Mexico, which are likely 7-to-10 times larger than officially published totals, squarely represent that third option. This Working Paper introduces preliminary findings from our research team’s industrial census across Mexico that has identified more than 200 discrete PRC-linked manufacturing and infrastructure investments worth an estimated $15 billion and potential future investments that could more than double that capital stock in short order.

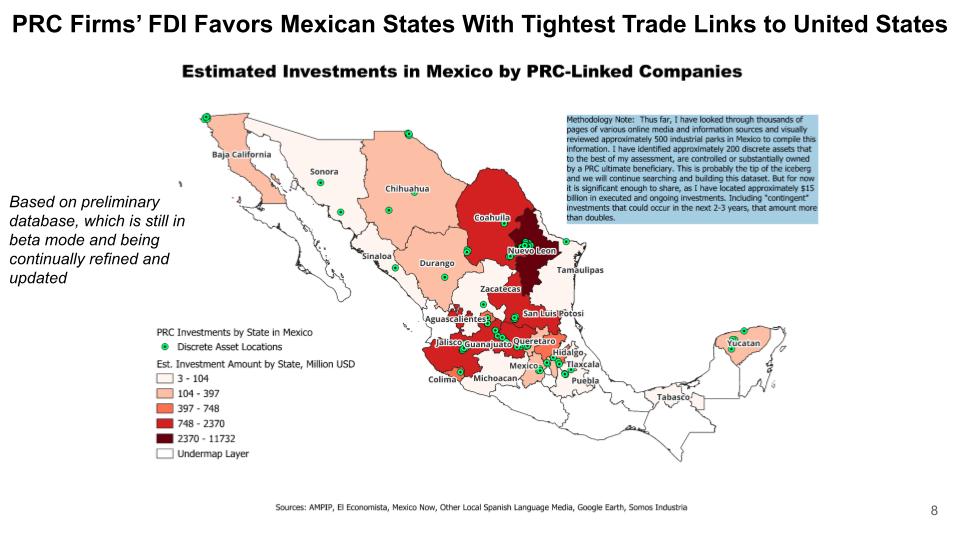

PRC-linked assets in Mexico cluster tend to cluster in the states with the tightest commercial and logistical linkages to the United States. Nuevo Leon stands out. In addition to ties with the US, these states–Coahuila, Guanajuato, Nuevo León, Querétaro, and San Luis Potosí–also host Mexico’s most competitive industrial and manufacturing clusters. These are also typically the places with the best access to road and rail linkages and low-cost inputs from the resource-abundant United States, in particular, natural gas.

Figure 1 — Estimated Investments in Mexico by PRC-Linked Firms, by State

Source: AMPIP, El Economista, MexicoNow, other local Spanish Language media, Google Earth, Somos Industria.

Note: Thus far, we have reviewed thousands of pages of various online media and information sources and visually reviewed approximately 500 industrial parks in Mexico to compile this information. We have identified approximately 200 discrete assets that, to the best of my assessment, are controlled or substantially owned by a PRC ultimate benficiary. This probably the tip of the iceberg and we will continue searching and buidling this dataset. But for now it is significant enough to share, as we have located approximately $15 billion in executed and ongoing investments. Including “contingent” investments that could occur in the next 2–3 years, that amount more than doubles.

II. Introduction and Methodology

This working paper is the first output from a larger project that aims to quantify investments made in Mexico by entities domiciled in, or with substantial beneficiary nexus ties to, the People’s Republic of China. We have compiled our initial data set by combing through thousands of pages of news and trade publication articles and a visual review of approximately 500 industrial parks in Mexico using Google Maps and its richly labeled urban and industrial topographies. We have also parsed official Mexican government corporation, and entity lists to cross check our findings.1

We acknowledge that PRC-linked investments come into Mexico under various jurisdictional guises, including, but not limited to, Hong Kong, Singapore, and even US subsidiaries of Chinese firms or US-based firms owned or controlled by PRC entities.2

Our core principle is to search for the ultimate beneficiary. If that entity is located in either the PRC itself, or Hong Kong (which now for practical economic and security purposes is a part of the PRC), then the entity makes it into our database.

We have sought to include investment data to the extent that is publicly disclosed. If a specific investment amount is not disclosed but we located actual physical plant facilities, we used $10 million as a placeholder value in the dataset. In many cases, this will be an undercount relative to the asset’s true economic value. For the two data centers that Chinese tech firm Huawei reports operating in Mexico, we assign a value of $100 million per data center. For all assets with unreported values that forced us to estimate, the parameters are likely to evolve as we continue to learn. At present, we are likely undercounting the true stock value of PRC-beneficiary investments in Mexico.

To determine the year an investment is credited to, we attribute it to the year a facility opens and commences operations. Investment begins before that as the project is under construction, but to attribute at a finer level of detail, we would need a level of disclosure that almost no foreign investors–whether PRC-linked or not–would provide. In defense of our present approach, many of the PRC-backed manufacturing assets are bought online rapidly.

From the date investments are announced until the time at which assets actually come online infrequently requires 18-to-24 months or less. For future- oriented projects that have been announced, but for which we cannot find evidence of capital deployment, we estimate based (1) on anticipated startup dates announced by project owners/sponsors (if available) or (2) our best estimate based on completion timelines for prior PRC-linked manufacturing facilities built in Mexico.

My colleagues Tony Payan, David Gantz, and I are continuing to locate and analyze at a high pace as part of our ongoing broad research project titled “The New Trade War: Mapping Strategic Impacts of PRC Investments in Mexico Amidst Intensifying US-China Competition.” Data-driven work is critical to ensure the US can effectively work internally and with its partners to formulate sound policy focused on the most relevant areas.

The dataset and map we have created thus far is likely just the tip of the iceberg. Expect updates. The project aims to create an evergreen map that we will periodically update as we locate new data.

III. What We Have Found Thus Far

Let’s first look at the data portion of this working paper. We have examined investments that (a) began operations in 2024 and earlier and (2) announced investments expected to come on stream in 2025 or later.

Our census of investments by PRC-linked firms in Mexico through 2024 suggests nearly $15 billion in cumulative investment. The number remains much smaller than the total foreign direct investment (FDI) stock that US firms hold in Mexico, which sits around $145 billion, according to the US State Department’s latest published assessment.3 However, the number is far larger than the officially reported PRC-origin FDI stock in Mexico of around $2 billion.

While our current figure is a multiple of the Mexican Government’s official numbers, it remains substantially lower than the estimate of approximately $22.5 billion promulgated by a leading Mexican scholar, Enrique Dussel Peters, director of UNAM’s Centro de Estudios China-México.4 Our research represents a key point of departure because we are making our working dataset publicly available to be scrutinized and hopefully, stimulate further conversation and feedback that will enable us to iteratively improve its analytical quality and comprehensiveness. We also publish the dataset as a service to policymakers on both sides of the border and in Canada as well.

Figure 2 — Estimated Annual FDI Into Mexico by PRC-Linked Entities Versus Officially Reported FDI From PRC

Source: AMPIP, El Economista, Google Maps, Hofusan, MexicoNow, Secretaria de Economia de Mexico, VYNMSA, authors’ analysis.

Note: Numbers for 2025 and beyond are forecasts based on disclosures by prospective investors and where necessary, our estimates.

The Snowball Effect: Coming Years Could See Much Higher Investment Levels

It is especially useful to think about how the PRC-linked investment stock numbers in Mexico could increase absent political constraints. Understanding the potential “natural” intensity of economic osmotic forces helps illuminate the drivers of political conflict as well as the relative plausibilities and probabilities of various resolution pathways.

China’s domestic manufacturing value added is now somewhere around $4.66 trillion annually.5 To translate that into a potential value of the underlying capital stock, consider the examples provided by the relationship of physical plant to enterprise revenues for several major global-scale industrial companies with robust financial reporting.

GM generated about $171 billion in revenue during 2023 using a physical asset base valued at about $50 billion (approx. 1/3 ratio).6 Toyota Motor featured a similar ratio of revenue to physical plant base value (1/2.5) in its fiscal year ending in March 2024.7 In 2023, Caterpillar generated $67 billion of revenue on a roughly $13 billion physical plant base (1/5 ratio) while Cummins obtained $34 billion in net sales atop a $6.2 billion physical plant base (1/5.5 ratio).8

Taking the most conservative range of these examples suggests that China’s capital stock in its domestic manufacturing base would be on the order of $1 of capital assets for every $5 in manufacturing output. Accordingly, a manufacturing base that outputs nearly $5 trillion per year could be worth at least $1 trillion in capital value. If even 10% of that aggregate stock sought opportunities abroad, $100 billion could be on the move. Going one step further, just ⅕ of that amount, or 2% of total roughly estimated existing PRC manufacturing capital redeployed into Mexico would double the estimated PRC presence there.

While these numbers are approximate at best, the investment trend of the next two years that PRC capital investments into Mexico could follow on an unconstrained course tracks the basic trajectory. Most of the investments we located over the past 15 years were smaller and flowed in incrementally after the US decision to impose tariffs on more Chinese goods in 2017. They tended to focus on auto parts and other sub-tier supply chains. However, the investments that some PRC firms, especially carmakers would “like” to make in 2025-2027 are far larger and by themselves would double our present tally. The fact that Washington will likely expect the Mexican government to take substantial steps to restrict Chinese investment in key sectors amplifies the political stakes.

Indeed, in 2024 the US itself took the very substantive step of prohibiting vehicles containing “connectivity systems” (consisting of software and/or hardware) made by entities owned or controlled by persons in “foreign adversaries,” a category that includes the People’s Republic of China.9 This formidable non-tariff barrier would require vehicles made in Mexico to exclude a major class of PRC-origin parts and associated software (think Bluetooth, WiFi, cellular, and satellite connectivity systems) in order to be exportable into the US. On balance, the resultant re-engineering of vehicles and supply chains likely dampens the enthusiasm of PRC carmakers that may have previously expected to export vehicles from a single production line in Mexico to markets all around North America, the EU, and beyond.

A meaningful portion of the present 2025 tally shown in our chart consists of estimates that assume capital deployment will occur this year. Given the incoming Trump Administration’s increasingly aggressive rhetorical stance toward Mexico, it is likely that amplified uncertainty will at a minimum defer these investments further into the future, drive them behind further layers of obfuscation, or even deter them entirely. But regardless, inbound PRC-linked investment in Mexico is a “here and now” challenge that is already transforming the politics around an expected 2026 USMCA negotiation.

We call these the “contingent investments.” Left to their own devices, PRC firms would probably make them and the Mexican authorities would likely allow them. But pressure from Washington to not follow such a course has risen sharply and contingent investments are presently a key competitive space. The stakes are large because while an auto parts plant might be a $25-to-50-million-dollar investment, an actual full-on vehicle factory like the one BYD, MG Electric, and others express interest in building could entail investing $1 billion or more per plant, a 20-fold or greater difference.10

If they built full assembly plants in Mexico, many of the Chinese automakers would likely also pull additional PRC-linked component suppliers into Mexico’s already formidable local manufacturing ecosystems, just as Toyota, BMW, and GM do in their respective operational areas in Mexico. The same would go for construction machinery makers like Lingong (a potential Caterpillar competitor) and its supplier base. And once the supplier base that PRC firms were most comfortable with was in place, other car and machinery makers that do not yet have a presence in Mexico could plausibly be attracted into setting up shop.

Incumbent firms would be affected but consumers might also benefit from lower final vehicle prices and to boot, the fact that many US auto parts firms’ supply roads already run back to China anyway could support an argument along the lines of “better to get the parts from a PRC-linked factory in Nuevo Leon than one in Ningbo.” We would expect something like it to be raised by interested parties.

Self-reinforcing dynamics of the type described above could drive a rapid and massive investment boom. The velocity of Chinese automakers’ penetration of the Mexican market over the past few years offers a loose analogy as to how fast Chinese firms can move once the environment becomes favorable and/or they are incentivized to do so out of necessity due to domestic overcapacity. Such a boom would also have secondary effects by straining infrastructure and the local labor pool—especially in regions that already have an advantage on these scores, the Northern states and the

Bajío region as well as the Valley of Mexico City. Re-onshoring by firms of any nationality at sufficient scale would likely create similar impacts, but without displacing US and ally country-based firms and the socially and politically important equities they underpin.

Figure 3 — Sectoral Breakdown of PRC-Linked Investments in Mexico Suggests Auto Parts Makers Think (Or Thought) Big PRC Automakers Were Coming to Mexico Too

Source: AMPIP, El Economista, Google Maps, Hofusan, MexicoNow, Secretaria de Economia de Mexico, VYNMSA, authors’ analysis.

IV. Why PRC Firms Are Interested in Mexico

Location behind the USMCA tariff wall in Mexico is akin to an “economic VPN” that allows preferential access to the massive North American market and indeed, every other market that Mexico has free trade agreements with. As one well-placed business facilitator puts it:

“The goal of everyone coming to Mexico is not just Mexico’s domestic market, but the entire North American trade zone…it is using a central manufacturing base to radiate into a large marketplace.” (“大家去墨西哥的目的,并不在于墨西哥的本地市场,而是整个北美自由贸易区…就是用一个制造业基地辐射一个大市场.”).11

This sentiment is reflected in multiple other statements from a range of commentators in Chinese, English, and Spanish, including the marketing brochure for the Hofusan Industrial Park near Monterrey, Mexico’s largest dedicated space seeking to attract PRC-linked manufacturing firms (Figure 4).

Figure 4 — Hofusan Marketing Brochure Excerpt

Source: Hofusan Industrial Park Brochure (2023 edition), hofusan.net.

Goods made in Mexico enjoy advantaged access to the all-important US market and the EU through the USMCA and Mexico’s free trade access to nearly 50 other countries. No country in Southeast Asia–China’s other global scale offshoring option–offers comprehensive privileged access to the USMCA zone and EU, which combined account for nearly half of global GDP and half of global imports (Figure 5). As such, these deep, high-income markets are indispensable for PRC exporters seeking to unload manufacturing output that continues to ramp up as part of General Secretary Xi’s “New Productive Forces” policy.

Figure 5 — Global Imports by Geographical Area, Percentage of Total

Source: World Bank, authors’ analysis.

Unrestricted access to site manufacturing facilities in Mexico would help China entrench US and EU reliance on its exports while undermining their efforts to remove PRC entities from key supply chains. The temptations for Chinese firms to use Mexico as a permissive access portal into the U.S. market were strong even as early as 2014- 2016. Consider the case of China Zhongwang, which at one point stashed a million tonnes of aluminum metal ingots in Central Mexico, likely destined for export to the U.S. under the guise of being “Mexican” aluminum (and thus exempt from tariffs) even though it actually came from smelters in China.12 Incentives for such bypass options are markedly stronger with substantial tariffs already in force, more on the horizon, and Chinese manufacturers’ growing need for markets abroad to absorb production that significantly exceeds domestic demand for key goods.

V. Strategic Background Context

China’s growing interest in Mexico fundamentally flows from geopolitics (U.S.-led efforts to reconfigure supply chains away from the PRC) and rising protectionism (the need to maintain access to the U.S. market).13 Despite flowery political rhetoric, markets

in Africa, developing Asia, and most of Latin America (aside from Brazil and Mexico) cannot absorb China’s growing manufacturing exports. Access to the U.S. and EU markets is paramount and relocating more manufacturing operations to Mexico facilitates both objectives.

Expanded PRC-linked manufacturing of high-importance goods in Mexico presents a significant and unprecedented challenge for the United States. These firms access much of their inputs from parties in China at rock bottom prices facilitated by a multi- decade industrial policy designed in part to crowd out competition and damage competitor economies.14 Now, this near-peer competitor can potentially site key sector manufacturing operations just across a well-connected border and the largest trading partner of the United States.

The situation is extremely politically salient because President Trump has repeatedly signaled that he takes the issues of trade and perceived PRC strategic intrusion in the Western Hemisphere very seriously. He also appears more inclined than his predecessor to take decisive actions to shore up the US strategic position in the Latin American region. The designation of Senator Marco Rubio as Secretary of State underscores this point.

The policy impacts of expanded Chinese manufacturing investment in Mexico are potentially tremendous. Politically influential American automakers who have committed many tens of billions to retooling their factories for producing EVs could face a flood of cheaper vehicles made by Mexican subsidiary factories of Chinese firms like BYD, which is rapidly expanding its market share in the continent, including Mexico. At a more general level, higher-end Chinese manufacturing firms could use large investments in Mexico to build an economic “blocking position” that raises the costs of anti-China industrial policies enough that they may become politically unsustainable over time.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in federal policy support for various green energy, transport, and other manufacturing enterprises in the US could be held at risk from PRC- linked firms domiciling factories in Mexico. Lest this sound overstated, consider that Volvo recently reported its made-in-China EX30 SUV will be sold at U.S. dealers starting in 2024 for $35,000 (pre-subsidy)—about $8,000 less than the comparable Tesla Model Y.15 The competitive challenge is massive and real.

Moreover, Chinese firms could entrench their intellectual property positions, while using their new “non-PRC” domicile to potentially renew access to foreign capital and technologies that might otherwise be inaccessible had they kept operations only in China. Such developments would undermine American attempts to break Chinese competitors’ holds on key supply chains, disadvantage the U.S. in the long-term bilateral strategic competition, and weaken U.S. influence in the Western Hemisphere while also sapping strategic bandwidth that might otherwise be deployed in Asia.

All these dynamics are congruent with PRC economic and national security grand strategy. In effect, expansion of PRC-invested manufacturing in Mexico is congruent with the core objectives of multiple Chinese Communist Party (CCP) economic and political grand strategy plans, including Made in China 2025, Dual Circulation, and using Community of Common Destiny concepts to weaken US-led economic and security relationship architectures.

A more significant PRC-linked economic presence in Mexico could facilitate the growth of competitor firms that undermine US industrial and manufacturing sector revitalization efforts. These PRC-linked entities would leverage preferential tariff treatment under the USMCA (even though preliminary evidence suggests much of their input content originates in China) to access the US market. They would also be able to access the EU and any other locations Mexico has free trade agreements with.

There is also a risk that importers of goods which are fundamentally “Made in China, Assembled in Mexico” seek Most Favored Nation (“MFN”) tariff treatment, which would mean import duties into the US that would be much lower than if the same goods were imported directly from China. Domain awareness facilitates differentiation and a key objective of our research is to help empirically enhance such visibility into PRC-linked manufacturing operations in Mexico.

Augmenting the manufacturing industrial bases of the United States and its key partners is a vital strategic priority. Equally critical is doing so in ways that minimize the ability of the Chinese Communist party to exert covert and overt extraterritorial controls and influences. Expansion of PRC-backed industrial activity in Mexico undermines both priorities.

Keeping The Strategic Challenge in Perspective

Strategic context also suggests that there are aspects of PRC manufacturing investment in Mexico that U.S. need not worry about, and in some cases, might even seek to encourage. For instance, if Chinese enterprises seek to produce toys, furniture, clothing, shoes, consumer electronics, auto seat belts, seats and other low-value added, low tech goods in Mexico, the economic and national security risks to the United States are virtually non-existent.

Those items are likely never going to be reshored. In fact, PRC-linked firms in low-risk sectors investing in Mexico takes capital out of the PRC, provides opportunities to attenuate Party influence, and creates jobs in Mexico (which may discourage illegal immigration and, in some cases, will result in parts and components and materials sourced in North America rather than in China (aided by robust rules of origin in the USMCA). Low tech Chinese components made by nearshored plants in Mexico can also help restrain consumers costs in the U.S. Industrial growth in Mexico driven by lower end PRC nearshoring may create opportunities for U.S. firms to participate at the higher end of value chains and also, to supply key raw materials such as natural gas. Indeed, there may be a path forward that entails setting red zones (high-end auto parts, telecoms, critical infrastructure) and green zones (low-end consumer goods) in which Chinese investments in Mexico would be opposed or not opposed by the U.S.

VI. Next Steps

Our ongoing study’s findings and recommendations will provide new and vital strategic value-add for policymakers, including:

- Continue quantifying how PRC investment in Mexico is and might continue playing out and the mapping of that investment

- Explaining the risks to the roughly $1.5 trillion per year US-Mexico-Canada trade relationship and the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) itself if Mexico comes to be seen as a Chinese economic and strategic backdoor into the US, and

- Setting forth an actionable menu of policy responses that the US, Canadian, and Mexican governments can employ to manage and pre-empt challenges to hemispheric opportunity and strategic stability.

The timing of the Project is critical because it will provide “first of kind” insights during a time in which all three USMCA countries are, or have recently undergone, leadership changes. Leadership transitions generate an especially intense need for objective, empirically grounded policy advice on critical economic and geostrategic issues the Project will address.

Notes

1 Government of Mexico. “Competitividad y Normatividad: Inversión Extranjera Directa.” Secretaría de Economía. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.gob.mx/se/acciones-y-programas/competitividad-y-normatividad- inversion-extranjera-directa?state=published.

2″Chinese Investment Is Pouring into Mexico.” Mexico News Daily. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/business/chinese-investment-is-pouring-into- mexico/.

3 United States Department of State. “U.S. Relations with Mexico.” Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.state.gov/u-s-relations-with-mexico/.

4 “How Much Is China Investing in Mexico?” Expansión, August 7, 2024. https://expansion.mx/economia/2024/08/07/cuanto-invierte-china-en-mexico. 5 “Tracking China’s Manufacturing Influence.” ChinaPower, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://chinapower.csis.org/tracker/china-manufacturing/.

6 General Motors. Annual Report (2024). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://investor.gm.com/static-files/0a93534d-729c-41ea-9d5e-e69ccad16803. 7 Toyota Motor Corporation. Form 20-F (2024). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://global.toyota/pages/global_toyota/ir/library/sec/20-F_202403_final.pdf.

8 General Motors. Annual Report (2024). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://investor.gm.com/static-files/0a93534d-729c-41ea-9d5e-e69ccad16803, Caterpillar Inc. Annual Report to Shareholders. Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.caterpillar.com/en/investors/financial-information/proxy- materials/annual-report-to-shareholders.html, Cummins Inc. SEC Filings: Form 10-K (2024). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://investor.cummins.com/sec-filings/all-sec- filings/content/0000026172-24-000012/0000026172-24-000012.pdf.

9 United States Federal Register. Public Inspection Document (2025-00592). Accessed January 28, 2025. https://public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2025-00592.pdf.

10 https://www.businessinsider.com/chinese-ev-companies-byd-mg-plan-factories- mexico-washington-concern-2023-12?op=1.

11 “〖投资墨西哥〗墨西哥,下一个世界工厂? [Investing in Mexico: Is Mexico the Next World Factory?].” 北美华富山工业园 [Hofusan Industrial Park], November 28, 2023.

Accessed January 28, 2025. https://www.hofusan.net/?mod=news-info&id=1159.

12 Scott Patterson, John W. Miller, and Chuin-Wei Yap, “Chinese Billionaire Linked to Giant Aluminum Stockpile in Mexican Desert,” The Wall Street Journal, 9 September 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinese-billionaire-linked-to-giant-aluminum- stockpile-in-mexican-desert-1473356054.

13 For an excellent taxonomy of global value chain reallocation decision factors, see Roberto Duran-Fernandez and Ernesto Stein, “A New Taxonomy of Nearshoring: Strategic Trends in Global Value Chain Reconfiguration,” Baker Institute for Public Policy, Working Paper, January 2025 https://www.bakerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/20250110-Taxonomy Nearshoring-WP.pdf (Pgs. 4-5).

14 Robert Atkinson, “We Are in an Industrial War. China Is Starting to Win,” The New York Times, 9 January 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/09/opinion/china- industrial-war-power-trader.html.

15 Norihiko Shirouzu and Chris Kirkham, “How Volvo landed a cheap Chinese EV on U.S.

shores in a trade war,” Reuters, 24 April 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/how-volvo-landed-cheap- chinese-ev-us-shores-trade-war-2024-04-24/.

Leave a Reply